This interview is a contribution to the David Suzuki Institute’s discussion paper, Silencing Science: How to Respond to Disinformation and Toxic Public Discourse. In 2025, the paper will support environmental and medical Groups in Canada through presentations, workshops and distribution of the paper, led by the David Suzuki Institute, with the aim that the paper's analysis and recommendations will help these groups counter disinformation more effectively.

James Hoggan, David Suzuki Institute – What are you currently working on?

Thomas Homer-Dixon - At the Cascade Institute, we have been working on a project focusing on disinformation and democracy; we’re calling it our “anti-polarization” project. Part of this effort focuses on Canadian identity, the health of democracy, political processes, and polarization. The disinformation component focuses on the underlying drivers of this pathology.

Many people point to the social media algorithms as the drivers, and while social media has clearly been a big part of it, and the algorithms don’t help, I have a somewhat different interpretation of these underlying drivers. The deepest source of the problem is that we have too much information; we’re overwhelmed by it. It started happening since the advent of the world wide web in the mid-90s and has been one of the most significant changes in the history of human civilization. We’ve increased the availability of information to the individual by at least hundreds of million-fold.

We’ve essentially made information generation and delivery costless and therefore economically frictionless. There’s no restraint on the amount of information we can store now, and there’s real-time computer power that allows for multi-player games that have tens of thousands, even hundreds of thousands of people involved simultaneously. Massive amounts of information have been digitized, libraries have been digitized, there are all these huge streams that are pouring out of social media.

It all piles up at the door of our cerebral cortexes, but the information processing capacity of the brain has remained basically the same. For instance, it’s interesting to look at the nature of modern entertainment compared to 30 or 40 years ago. Movies: the clips are much shorter, the pace is much faster, and the information delivery comes in a much higher kinetic rate of bits and pieces of information. Plotlines are switching back and forth all the time. Our brains have rewired themselves to a certain extent to allow for hyperlinking. We hyperlink in real time, not just on the web. We are jumping between things all the time, and one of the results is that processing of any particular bit of information is much more superficial.

We don’t spend enough time going deep on any particular topic, and there’s been a compression of message length because there’s so much information, and we’re trying to move through it so fast – too long, don’t read. In that kind of environment, the way you get attention is through ramping up the emotional impact of the message.

There are four truly powerful emotions: disgust, fear, anger, and awe, which is a relatively positive emotion. But the big ones that keep people’s attention, that get them to look at the TikTok feed, or the Facebook page, or the Twitter/X feed, are fear, anger and disgust. They’re native emotions, and they’re always directed toward potential threats. Exploiting them in one’s messaging is fundamentally divisive, but it’s inevitable in an environment where we’re all overwhelmed. If you want to get your message heard, you have to push certain emotional buttons.

There’s another aspect to this that I learned following a conversation with the former COO of Shopify, Toby Shannan. He’s a complexity geek, board member of the Santa Fe Institute, and a supporter of the Cascade Institute. We have some very strong mutual interests in forces that are driving up complexity in our societies. When he was at Shopify about eight years ago, he noticed that the support staff the company required was growing much quicker than the client base; in fact, it was increasing unsustainably fast. When he looked into it, he realized that Shopify is a platform that integrates disparate elements of a web: different paid platforms, and places where people could advertise their products. Shopify is making the user client’s engagement with the web as seamless and smooth as possible by trying to do all the interface work between various components on the web.

Toby therefore developed what he calls an “interface theory,” which is a theory of the cognitive load every time you cross an interface between one system and another. I won’t go into the details, but we’re writing a scientific paper together, because we are trying to mesh my ingenuity-gap theory (from the early 2000s) with his interface theory. His idea is enormously powerful and has several compelling implications. Among other things, it implies that in a situation where you have an overwhelming abundance of information, if there’s significant cognitive load in dealing with other agents of the system who are different from us, then you will automatically turn to similar agents, in order to manage the cognitive load.

Whenever you try to talk to somebody with a different political perspective, or working in a different profession, or from a different generation, more of our cognitive resources are required. If you were to do a functional MRI of a person’s brain in this situation, you’d see it lighting up as parts of that brain consume more glucose; they’re working to cross that cognitive boundary with the other person. Shopify tries to maximize inter-operability among diverse systems, so they want to make all these boundaries disappear. But Toby found that the boundaries were getting in the way and demanding a huge amount of support staff underneath the surface to help people navigate them.

When you think about it, in our highly networked world now, we’re crossing boundaries all the time, and we’re absolutely overwhelmed with information. In that environment, there’s a greater incentive to turn to “like” rather than “unlike” entities. We stick to what we know, because we can process the information arising from that engagement faster. We connect and engage less and less with those who aren’t like us. That thickens boundaries between disparate people and groups, and then those boundaries become political and social opportunities for opportunistic actors to create fear, anger, disgust, and distrust. The negative unanticipated consequence of connecting everybody has been that we have become fundamentally more disconnected.

The result is what I call epistemological or epistemic fragmentation. People are living in isolated realities because it’s hard for them to manage the amount of information they encounter. They turn inwards to their little communities because “at least I understand these folks and they understand me.” It’s an unmitigated disaster. At a time where we face the worst problems that humans have ever faced, we have a collapse in shared understandings of the world. That’s an important part of my theory of what’s going on.

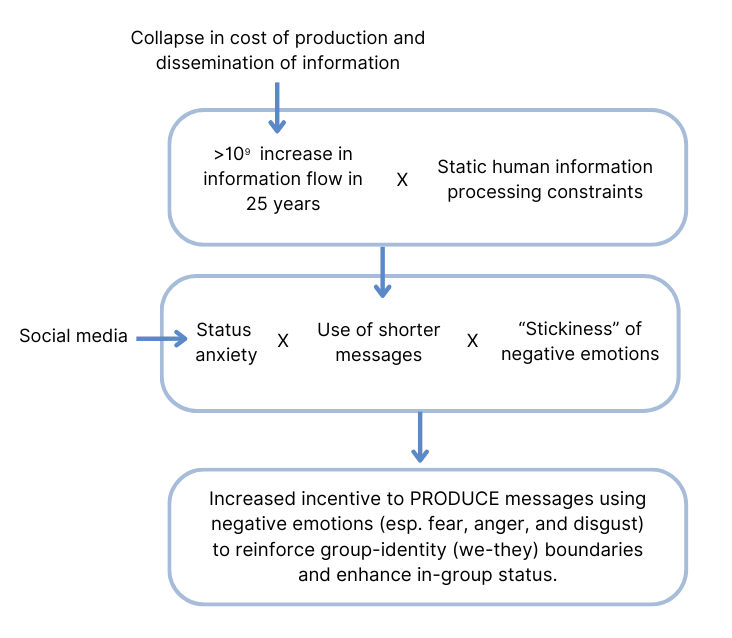

Here is a diagram that captures the first of those two processes: how information overload creates incentives to ramp up the emotionality of our messages, resulting in thickened boundaries between groups.

JH - I tend to get stuck in the idea that it’s bad actors that are doing it.

THD - The bad actors take advantage of a particular information ecosystem that we’ve created through technology. I put the information ecosystem first, and then it selects for bad actors, or gives them opportunities that they wouldn’t otherwise have.

What this diagram is about is us being overwhelmed, and as deliverers of messages, the only way we can get attention is to increase the emotionality of our messages. We have to drop down into more primitive segments of the brain to trigger things that get attention.

The boundary argument, or “interface theory,” is somewhat different. It basically says that, as receivers of messages, when we are thinking about who we’re going to engage with, if we are overwhelmed with information—a situation of cognitive overload—we’re more likely to try to avoid the cognitive work of crossing boundaries. One of the boundaries here is the extra effort it takes to communicate with people with different values or beliefs, compared to someone who thinks similarly to us. Overload leads to avoidance, which results in a thickening of boundaries between groups and increases what network researchers call homophily, the tendency for people to gravitate more towards people who are similar to them. Because bandwidth and cognitive capacity are scarce, we have to parcel out resources carefully. In a world where information is abundant, and the cognitive load overwhelms our brains, it’s easiest to go to the sources of information that are most immediately accessible and the most similar to the way we already think.

A big part of the problem is that today’s abundant information environment strongly enables both of these processes. A lot of the time, problematic information comes from sources that not only think similarly to you, but also have some kind of emotional trigger, such as hate, anger, fear, or disgust. This information environment selects for the worst actors in the system, in terms of people’s abilities to exploit and create divisiveness and unhealthy conflict.

What I’ve just described is the cognitive component in a four-part causal model we have developed as part of our anti-polarization project at the Cascade Institute. The other three pathways in the model consider economic, political/institutional, and cultural factors. You can get more information about the larger model and the anti-polarization project here.

JH - This is normally talked about as a good guy/bad guy situation, but that doesn’t help, if it’s not the cause.

THD - It plays on anger and fear. We always want to find the actor who’s responsible for our distemper or why things aren’t going well. We go through the simplest causal model that appeals to our emotional repertoire. We always want to look for the bad guy.

My starting assumption is that people’s moral compasses are more or less normally distributed—as in a bell curve—and that people who are really bad or morally compass-less, are in one extreme the tail of the distribution and are fairly unusual, just as people who have very strong moral compasses are very unusual and are in the opposite tail.

Most people would like to be good and are good most of the time. But when they’re scared, that mean of the distribution can easily move towards the nasty end, and there are a lot of folks at the tail of the distribution who are very happy to drag them in that direction. I don’t know what the answer is, but I think we’ve got to get the diagnosis right.

JH - I think that’s right, you’ve got to get the diagnosis right. It’s hard to communicate if you misunderstand the actual barriers to communication.

THD – So interface theory is Toby Shannan’s idea. He noticed that as you cross a cognitive boundary to engage with another system, which could be another individual, another institution or another technological system, you go through three stages that involve increased cognitive load.

The first presents, for example, as you approach a website. The first thing you do is a kinesthetic interaction; you are pushing buttons, checking boxes and the like, as if you’re in a physical environment. This interaction doesn’t require a lot of processing; most stuff should be intuitive and easily grasped. This would be the equivalent of having a conversation with someone you really understand and know very well, and it’s an almost seamless interaction between your two heads.

The next stage is when you can’t get the information you need, or you are not connected to the system in the way you want to be, so you have to go to a page with some text. At that stage you are handing the problem from one cognitive module in your brain to another. You could do an FMRI scan of the brain, and you’d probably see other parts of it light up, and the glucose consumption in the brain increase significantly.

If that doesn’t work, you have to actually talk to somebody. So you go to a chatbot or a chat box or end up on the phone with somebody. Now you are in a communicative environment where you have to explain the problem and then there’s back and forth questions and verification of your identity and all that. The cognitive load is skyrocketing at that point.

Toby pointed out that if you consider all these actions as independent cognitive events; then you measure the cognitive work involved in each; and finally you chart each event as a separate dot on a graph with cognitive load on the vertical axis going from least at the top to most at the bottom, you want an upside-down pyramid that’s as shallow as possible. In other words, you want most of the interactions during a visit to a website, for instance, to have a relatively low cognitive load, with very few, if any, involving a high cognitive load.

You don’t want people to get to the point where they have to talk to somebody in support. You want to have what he called a “plate,” rather than a “spike.” In reality, Toby said a lot of organizations are getting an “hourglass” or a “goblet” pattern in their online interactions, with an increased number of individual engagements down at the bottom with a high cognitive load. The surface stuff on the website doesn’t work, so people end up talking to a lot of support staff, which increases the number of dots in the bottom part of the hourglass.

In our paper together, we use the example of an airport to illustrate the ubiquity and nature of interfaces. In airports, you’re crossing between systems all the time. You walk in and the first thing you do is go to a ticket desk, or you go to a kiosk, and you punch in your booking reference number; it’s fairly kinesthetic, but it’s not working very well. So an airline agent is right there to explain it to you. Then you go into the security system, and there’s a different set of operating procedures, lots more signs to read, a very specific set of protocols for taking stuff out, putting it in bins, things like that.

The point is that every boundary requires us to think, and sometimes think a lot, and it slows us down. This is the major reason why—in terms of my old ingenuity gap theory, which says that the rising difficulty of our problems is outracing our collective capacity to supply good solutions—we’re not solving problems effectively. Today, so many of our problems require us to bring knowledge together from an enormous number of domains. We need to bring climate scientists together with economists, together with public administration folks, together with epidemiologists. They all operate in their different ontological worlds, different languages, different ways of ordering reality, and even if they want to talk to each other, we just don’t have the mental capacity to do it.

JH – That’s interesting, because when the public relations business started somewhere around 1930, two of the big insights were that emotions communicate better than facts, and keeping it simple is better than complicated facts.

THD - That’s exactly what I’m saying.

JH - But it’s worse now because the amount of information that we’re confronted with is far more overwhelming than it was in 1930.

THD – Yes. Two things are happening. One is the vast gain in information availability. The amount of information we have at our fingertips is billions of times higher than it was 25 years ago.

The other is the proliferation of boundaries around us. As we’ve linked ourselves together more in the world, the number of boundaries has increased faster than the number of entities in the system. The rule of thumb is that the number of links in a network increases as the square of the number of entities in the network. Each one of those links creates a boundary possibility.

Robert Dunbar did a famous bit of anthropological research and came up with what is now called the “Dunbar Number.” He looked at the cranial capacity of hominid species going back to apes and correlated that with archaeological and anthropological evidence on the size of the standard community group across those species. There’s a very close correlation. The bigger the brain, the more we can track other members of the community so that we can more-or-less understand them all, anticipate their behavior, and engage with them strategically and communicatively.

The Dunbar Number for human beings is about 150. It’s way above other hominids; for instance, for Homo Erectus it’s about 90. These are classic studies. I don’t know how many people I’m in touch with, but my guess is it’s in the thousands. In that environment I have to make a choice between contacting Joe or Jane. I’ve worked with Jane a lot and it’s easier for me to communicate with her. Joe might be an interesting person, but things are just not meshing, or he’s in a different discipline, something like that. So, with my very limited scarce bandwidth in an environment of overwhelming connectivity and information, I’m going with Jane.

JH - I’ve been reading about propaganda and how it works. It seems that the heart of propaganda is the polarization and division that comes from the emotions you just described.

THD - Fear, anger and disgust. Disgust is really important. Former US president Trump uses the word “disgusting” all the time. It’s one of his go-to locutions, and clearly disgust is a highly salient emotion for him. He is neurotic about cleanliness and cleaning his hands; he won’t shake people’s hands. The disgust sensitivity has a very high correlation with radical conservatism. The bad actors leverage these emotions. They know exactly what they’re doing.

JH - Marshall Ganz teaches emotional dialogue, where you counter negative emotions with positive emotions. The positive emotions would be hope, maybe empathy or awe. What do you think about that?

THD - Negative emotions have a leg up, because once you establish that you can’t trust other individuals in your social milieu, then you’re in what international relations theorists would call a “self-help” situation; you have to start protecting yourself. In the US, this can mean buying a gun, and a lot of liberals are buying guns now. They don’t want to, but they are.

As soon as everybody has devolved to protecting themselves, they’re contributing to the fear in the group. This is a vicious cycle. Complexity scientists would call it a positive feedback loop. It’s the consequence of the disintegration of order, or what international relations theorists call creation of “anarchy” in the system.

Governments exist to provide sufficient coercive force, controlled by a central entity, to boost the likelihood that you can trust this other person, you don’t have to fear them, because if they hurt you, they’re going to be punished. But once confidence in that overarching sense of order, and the incentive system of coercive punishment, disappears, then you’re on your own, and once you’re on your own, it doesn’t matter how liberal you are, how much people say “you should just love your neighbor.” People will say, “yeah, I would love to love my neighbor, but I don’t know if they’re going to blow my head off, so I have to pack a piece.” That’s where the US is now with its 400 million guns.

MS – We interviewed Andrew Hoffman, who wrote a book on drivers of climate change denial. He talks about using what he calls cultural brokers as a way to convince people that climate change exists, and to more effectively communicate science generally. We think one of the contributors to the issues around disinformation is sometimes how scientists communicate. We saw some of this with covid-19 in terms of being told to trust the science, and then messages about the science changing later on. So we think effective responses to disinformation should also involve how to communicate more effectively, and this cultural brokerage idea may help with this, which seems to echo some themes in your book Commanding Hope, in terms of being strategic about learning where other people are coming from, what their values and beliefs are, and how to adjust messaging according to those things.

THD – Yes. You have to pitch your message to the temperament of your audience. And we can do a much better job of explaining to people how science works. Science is not about generating facts, it’s about reducing uncertainty, especially with these complex systems. Findings or conclusions are constantly revisable, constantly falsifiable. It is a search for truth, but truth is always corrigible, it’s a provisional truth. People don’t understand that, because they want solidity in their lives, especially as things get scarier. “Just tell us what to do about this virus, what are we supposed to do?” And the scientists are saying, “well, there’s some evidence here, and there’s some evidence there,” and the people are saying, “no, I don’t want to hear this, just tell us what to do.” So they end up being told what to do, and the evidence changes, and two months later they’re told to do something else.

One can understand why it went off the rails, but it’s partly because people don’t understand the nature of science. For cultural brokers, Andrew Hoffman was probably talking in terms of people who can do a better job of communicating, because it’s a cultural issue. It’s a culture of science, and people have such wild misunderstandings of science. The University of California, Berkley has a website and downloadable pdf with lessons on how science works.

Thomas Homer-Dixon is Professor Emeritus and founder of the Institute for Complexity and Innovation at the University of Waterloo, founder and executive director of Cascade Institute at Royal Roads University, and former director of the Center for Peace and Conflict Studies at the University of Toronto. His research focuses on threats to global security in the 21st century, and how organizations and societies can better adapt to complex economic, ecological and technological change. Author of multiple award-winning books, his most recent, Commanding Hope: The Power We Have to Renew a World in Peril, explores how honest, astute and powerful hope can help foster the agency needed to address the many daunting challenges faced by humanity today. He is a contributor to outlets including the New York Times, The Globe and Mail, Foreign Affairs, Foreign Policy, Scientific American, The Washington Post, and The Financial Times.