Thomas Homer-Dixon

The Version of Record of this op-ed was published in the The Globe and Mail.

Thomas Homer-Dixon is executive director of the Cascade Institute at Royal Roads University and professor emeritus at the University of Waterloo.

In a few days we’ll experience an abrupt shift, a sharp inflection point, in human civilization’s trajectory. In the past such shifts – caused by events like wars, pandemics, economic depressions and technological breakthroughs – have almost always caught us unawares. What makes this coming shift exceptional is that we all know exactly when it will happen and exactly what will trigger it.

Following his inauguration at noon Eastern Standard Time on Jan. 20, the new President of the United States, Donald Trump, will review military troops from the Capitol’s East Front steps, lead the inaugural parade to the White House, and watch the proceedings from the presidential reviewing stand. He’ll then sign up to a hundred executive orders.

We can expect the orders, backed perhaps by one or more declarations of national emergency, to curtail immigration and ramp up deportations, raise tariffs, ban federal funding for DEI programs, pardon some Jan. 6 convicts, end support for electric vehicles, remove the United States from the Paris climate agreement (again) and the World Health Organization, and, quite likely, cut federal money to schools permitting transgender girls to compete in female sports. Another order will probably reinstate the Schedule F classification of civil servants, which Mr. Trump promulgated late in his first term and President Joe Biden rescinded, allowing the new administration to replace tens of thousands of federal civil servants with loyal appointees.

All dramatic stuff. Ultimately, though, the orders’ specific content will be far less momentous than the occasion’s aggregated causal force – a force that, once unleashed by those signatures, will propagate through time to the farthest reaches of humanity’s future. Historians will look back on those minutes as the start of what Princeton sociologist Paul Starr calls a “constitutive moment” in world history. This is a period, Dr. Starr writes, “when power looks to new ideas, and new ideas find their way to power” and when “institutions are fundamentally and durably redesigned.”

Constitutive moments are a special kind of historical inflection point. Powerful actors like U.S. presidents always operate within a constellation of macro-trends, cultures, institutions, and social and political alliances. But during constitutive moments, they have a rare opportunity to radically reconfigure that constellation because the usual constraints on selecting from, combining, and adjusting its elements are greatly weakened. The systems they’re operating within are abnormally susceptible to massive change.

Leaders who effectively exploit these opportunities can create not just profoundly new ways of doing things, but also new ways of seeing things. A constitutive moment shifts our deepest understandings of the world and its possibilities, and to the extent that these understandings partially create the world around us, it shifts our world’s essence itself.

As the “reconfigurer-in-chief” at this particular moment, Donald Trump will be, in philosopher Georg Hegel’s terms, a world-historical figure. If he brings an end to the American democratic republic, he’ll unequivocally rank alongside Washington and Lincoln as among the most significant presidents. But he’s likely to be far bigger than even that. We might not want to concede the fact, but Mr. Trump will probably, in time, take his place in the pantheon of history’s most consequential figures.

This is, admittedly, a contentious claim. Early last fall, my research team at the Cascade Institute, while analyzing the risks that a second Trump presidency might engender, split on exactly this issue. Some team members argued cogently that Mr. Trump’s rise reflects deep stresses that would be expressing themselves in similar ways if he weren’t around.

But although economic, geopolitical, technological and environmental stresses have long been pushing us toward global tipping points, in his second term Donald Trump will be a uniquely powerful accelerant of these stresses in uniquely dangerous ways.

This will be true even if his orders don’t achieve what he intends, and he ultimately makes a complete mess of things – maybe even more so then. Indeed, the essential paradox of Mr. Trump’s impact is that he’s constantly generating “certain uncertainty.” We know for sure that he’s going to create disorder – he’s already doing so, and he’s not even President yet – partly because he’s so mercurial. But Mr. Trump has an additional, special power. He has a preternatural ability – almost like a powerful acid – to dissolve the institutional, legal and normative constraints around him, creating the conditions for a constitutive moment. And as those constraints erode, future possibilities multiply exponentially.

Certain uncertainty, in the present case, means that we can see clear as day, rushing toward us, the inflection that Mr. Trump is about to cause, but we can’t see what follows that point – specifically what will be “locked in” once this constitutive moment has passed. The future that Mr. Trump is going to create is largely indiscernible.

Still, the inflection will probably send humanity in an extraordinarily perilous direction, for three reasons.

The first is ignorance. Donald Trump, many of his advisers, and a large slice of his followers are contemptuous of expertise, especially credentialled expertise; they’re ill-informed about history and oblivious to scientific fact. But they’re nonetheless entirely persuaded of their brilliance. That’s a potentially deadly combination, because genuine expertise still matters, a lot.

It may be true that the success rate of our expert elites in resolving (or even barely managing) our various social, health, economic and technological problems has declined over the decades, as those problems have gotten steadily more complex. But as our problems get harder, the answer is to make our societies smarter, not stupider. We need to push our experts to do better, and push our politicians to listen to them more, not push our experts away from the centres of power and responsibility.

This contempt for expertise will do most harm when the Trump administration is obliged to make high-consequence decisions under extreme time pressure, as will inevitably happen. During the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, after U.S. intelligence agencies found that the Soviets were installing nuclear-capable missiles in Cuba, president John F. Kennedy drew on his cabinet and staff to create a small team of extraordinarily capable advisers (the “ExComm”). That team methodically searched for and weighed alternative U.S. responses. Kennedy, having learned from the Bay of Pigs disaster the year before, told some ExComm members to act as devil’s advocates; they were to deliberately challenge the group’s emerging consensus in order to fully test its final decisions. My brain breaks when I try to imagine Mr. Trump doing the same sort of thing.

The second reason Mr. Trump is likely to send humanity in a perilous direction is the nature of his relationship with his followers – his “base.” This relationship practically guarantees his radicalism won’t moderate over time. In fact, it’s likely to feed on itself, as resistance empowers it.

That’s because Mr. Trump has another preternatural ability, one that’s closely linked to his capacity to dissolve the constraints that would bind an ordinary political leader. As many have noted, he’s able to express and mobilize his followers’ negative emotions (fear, anger, and disgust) in ways that make him, in essence, a cult leader. But what’s not widely appreciated is the mix of factors that renders his particular Kool-Aid so incredibly potent.

It consists of a triplet of personality features: Mr. Trump’s malignant narcissism, his off-the-charts disinhibition, and his extraordinary capability as a salesman.

Mr. Trump’s narcissism means he desperately seeks adulation. That’s the underlying emotional impulse that so many close observers – including his niece, a clinical psychologist – have highlighted. This deep drive then couples with extremely high psychological disinhibition. This latter trait, which is almost certainly worsening with age, permits Mr. Trump to do anything necessary, without shame, embarrassment, or moral quandary, to get people to adulate him. And finally, at the core of his remarkable sales ability is a wickedly astute intuition for how to reach people – the buttons to push, the levers to pull – where they emotionally want to be reached.

This psychological triplet has helped Mr. Trump turn himself into a bigger-than-life expression of the collective id of a large portion of the American population. At a moment in history when forces beyond their control have made many Americans deeply insecure, Mr. Trump has become the walking-talking projection of people’s frustrations, fears, anger, cynicism and desire for vengeance. And they love him for it, because in dissolving America’s normative constraints, he licenses them to say or do the same things themselves.

A vicious cycle has now kicked in. As Mr. Trump performs on America’s stage – creating disorder, fueling uncertainty and instantiating people’s fearful, angry, vengeful id – he’s vastly exacerbating society’s divisions and polarization, in turn making people angrier and more fearful. Like a successful parasite or pathogen, he’s creating conditions that promote his own survival and propagation.

Martin Wolf, the chief economics commentator at the Financial Times, and a wise observer of human affairs, put it to me this way recently: “Demagogues are common, but demagogues who are geniuses are exceedingly rare. Trump is a genius as a demagogue.”

The vicious cycle is likely to intensify, not abate, over the coming months and years. Mr. Trump now sees himself at power’s apex. He was Time magazine’s Person of the Year and rang the opening bell at the New York Stock Exchange; he’s being fawned over by the world’s wealthiest man. He believes he has an “unprecedented and powerful mandate” to govern – despite the fact that he won less than 50 per cent of the popular vote and only 1.5 percentage point more of the vote than his opponent. But his party controls both houses of Congress; the Supreme Court has essentially conferred immunity from prosecution upon him; he’ll soon have at his feet a terrified and compliant public service; and with targeted purges, he’ll probably subordinate both the Department of Justice and Department of Defence to his will. All the “inhibitors” that surrounded his first administration are falling away.

Without guardrails, and inflamed by a sense of righteous, inevitable entitlement, Mr. Trump will become increasingly extreme, as his policies don’t work, and his incompetence creates mess. His administration will flood the landscape with disinformation, cooking the statistics on its performance, suppressing federal agencies that might provide unadulterated evidence on worsening trends, and using the power of the federal state to attack scapegoats and critical media. It will order the military to suppress protest, and it will aim to destroy, either directly or through mobilized supporters, anyone in its way.

There’s one further reason why the coming constitutive moment will send us in a perilous direction, perhaps the most important of all: Today’s world is primed for massive change. Its tightly linked economic, geopolitical, technological and environmental systems are under staggering stress and potentially close to tipping points. If they’re pushed beyond critical thresholds, they could swiftly change their basic structures and behaviours, the way tectonic stresses in the Earth’s crust sometimes erupt in colossal earthquakes.

At the Cascade Institute, we’ve identified more than a dozen discrete, long-accumulating global stresses, including climate heating; declining economic growth and rising economic inequality; worsening authoritarianism and polarization; increasing risk of food crises and zoonotic viral pandemics (like COVID); and growing tension between the U.S. and China, as they compete for hegemonic influence.

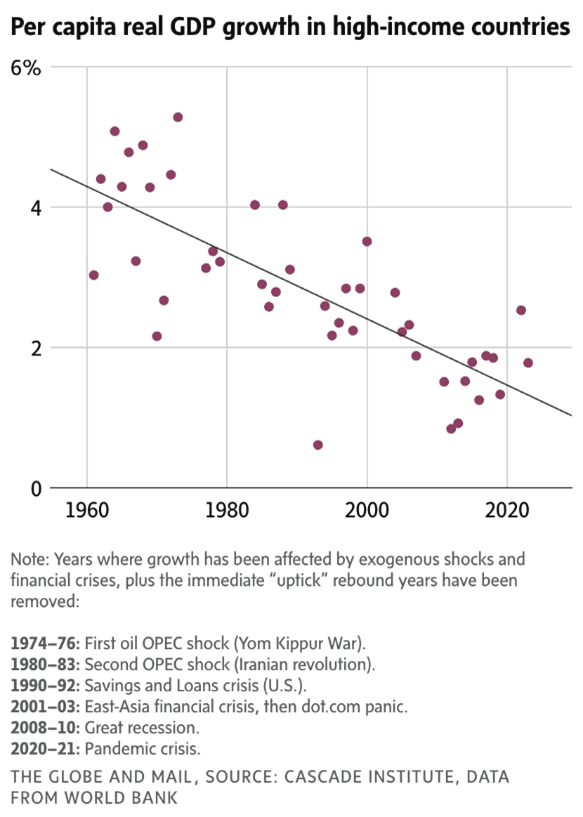

Two charts underscore these stresses’ duration and power. The first shows how per capita annual economic growth (after inflation) has steadily declined in wealthy countries for the past 60 years, from over four per cent to barely one per cent. (To clearly reveal the trend, we’ve removed anomalous years, defined as those where financial crises and exogenous shocks like the pandemic significantly affected growth.)

The causes of this long-term decline are many and complex, ranging from population aging and the leveling out of female workforce participation to the IT revolution’s surprisingly weak productivity boost. But whatever the causes, falling economic growth had a major effect on these societies. With less wealth to share, zero-sum thinking gained ground. Powerful groups torqued institutions and rules (tax breaks, subsidies, and the like) to protect their slices of the pie. Politically and economically weaker groups paid the price as incomes stagnated, and wealth gaps between them and the rich widened into chasms. Resentment of outsiders, such as immigrants, who might tap the shrinking surplus soared, as did debt, as household and national governments compensated for ever-more straitened circumstances by borrowing from future generations.

Declining growth, widening inequalities and rising economic precarity are unquestionably among the most powerful factors behind the surge in populist authoritarianism in wealthy societies over the past decades. Donald Trump has excelled at leveraging these trends to his benefit.

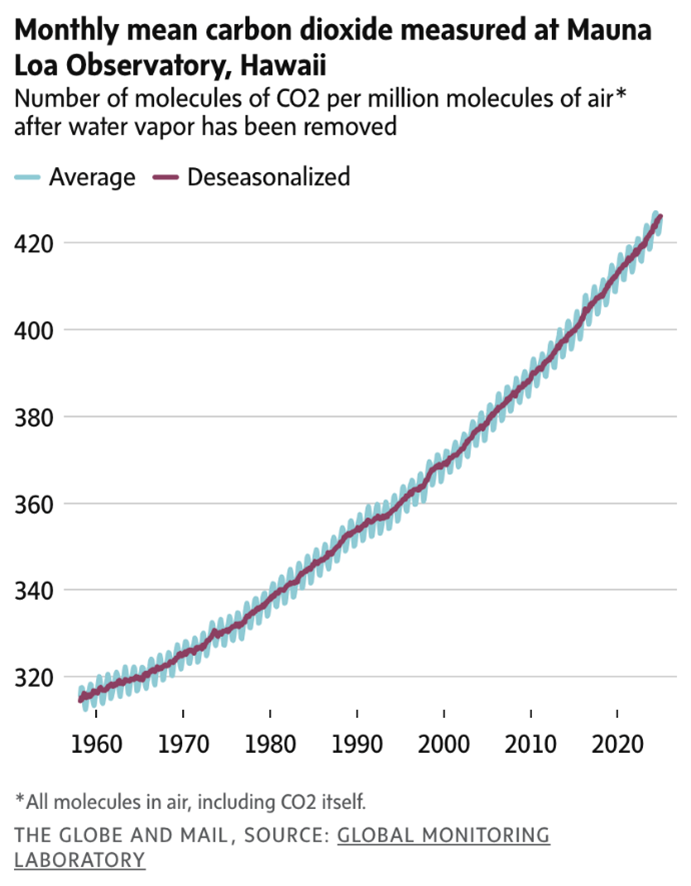

The second chart is the famous Keeling curve, which shows the relentless rise in the concentration of carbon dioxide in Earth’s atmosphere, as measured on a Hawaiian mountaintop. This trend correlates directly with our planet’s rising energy imbalance, now amounting to over a watt per square metre over Earth’s entire surface – or the equivalent of over half a million Hiroshima bomb’s worth of extra energy injected into our air and oceans every day. This extra energy drives increasingly extreme droughts, heat waves and storms afflicting our world.

Climate heating’s impacts – city-destroying wildfires, massive flood damage to property and infrastructure, depressed crop yields and increased illness from heat and opportunistic pathogens – are already sucking trillions of dollars out of the global economy and certainly weakening overall economic growth. But these impacts’ psychological toll is just as telling. Even if people won’t admit climate change’s reality, they sense that the weather is becoming more extreme and that the natural environment around them is behaving more erratically, and that really scares them.

And it’s here where my Institute colleagues are undoubtedly right: Mr. Trump is both a product and accelerant of these manifold stresses. He feeds off the precarity and fear they generate, while simultaneously worsening the stresses themselves. His tariff policies will further weaken global growth; his antagonism toward climate science and policy will cripple humanity’s efforts to slow heating; his withdrawal from global multilateral health organizations will make the next pandemic more severe; and his affinity for autocrats, disdain for national sovereignty, scorn for alliances, and proclivity to speak in the language of force sharply raise the risk of major war. In each way, he drives humanity closer to a precipice.

Three years ago I warned in these pages that Mr. Trump’s return to the presidency could fatally weaken U.S. democracy, producing a right-wing dictatorship by 2030. Many thought that was an outlandish claim then, but it’s an almost commonplace observation now.

I also asked the question: What should Canada do to prepare? We’ve squandered the time since, so we aren’t remotely ready for the shock Mr. Trump’s signatures will soon unleash.

Our country is now in grave peril. Mr. Trump seems intent on fracturing our federation, by using tariffs and other measures to create an economic crisis severe enough to stimulate secessionist movements, particularly in Alberta, where polling indicates that 30 per cent of the population already thinks the province would be better off as a U.S. state. If a charismatic advocate, well-funded by the friends of the Trump administration, can convince 51 per cent of Albertans to vote in a referendum for secession, does anyone doubt that the U.S. President would demand that the rest of the country let the province leave? And without Alberta, Canada is finished.

Experience shows that Mr. Trump usually backs down when an opponent shows a spine. But it’s hard to have a spine when you don’t have a head. And at the very moment of greatest danger for Canada, we’re close to headless. In this emergency, we need something akin to a national-unity government or an all-party “war cabinet.” But with a few notable exceptions, such as Foreign Minister Mélanie Joly, who decided service to her country was more important than a run at Liberal leadership, our national political class is largely AWOL, unable to set aside their hostilities and ambitions to draw together for our larger good.

In the next federal election, Canadians will need to decide how much we’re prepared to pay for our independence – and in what currency.