The Cascade Institute is a Canadian research centre at Royal Roads University, in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. It addresses the full range of humanity’s converging environmental, economic, political, technological, and health crises.

Outstanding complex-systems scientists, including experts in rapid change in social and cultural systems, conduct the Institute’s research. Working in small, nimble teams and guided by two core scientific premises, they produce applied, actionable knowledge at speed.

Our activities are divided into two mutually reinforcing streams:

Anticipating Pernicious Cascades

Researchers analyze the interactions of risks and crises across different systems to understand how they exacerbate one another, thereby identifying inter-systemic risks that are typically missed by conventional horizon-scanning and foresight methods.

Triggering Virtuous Cascades

Researchers identify high-leverage interventions that could produce a virtuous cascade—a sequence of causally linked, nonlinear changes within a system that generates social benefits and steers humanity towards a more just and resilient future.

Using advanced methods to map and model complex global systems, we analyze interactions between systemic risks to anticipate future crises and identify opportunities for high-leverage interventions in social systems.

By acting as a network hub and catalyst among scientifically aligned research entities around the world, we help to draw together, focus, and amplify expertise.

And we provide governments, businesses, civil society groups, and frontline actors with a better understanding of the world’s problem landscape. We then help these leaders develop specific interventions to trigger a rapid shift in humanity’s trajectory towards fair and sustainable prosperity.

Non-Partisan Orientation

The Cascade Institute is non-partisan and ideologically non-aligned. It promotes fair and sustainable prosperity for all humanity, understood according to the criteria and norms set forth in the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The Institute engages in both pure and applied research, and its staff and researchers are exclusively responsible for deciding the scope and foci of this research. The Institute’s applied research—including training of practitioners in intervention strategies and field observation of intervention results—is targeted to further specific SDGs.

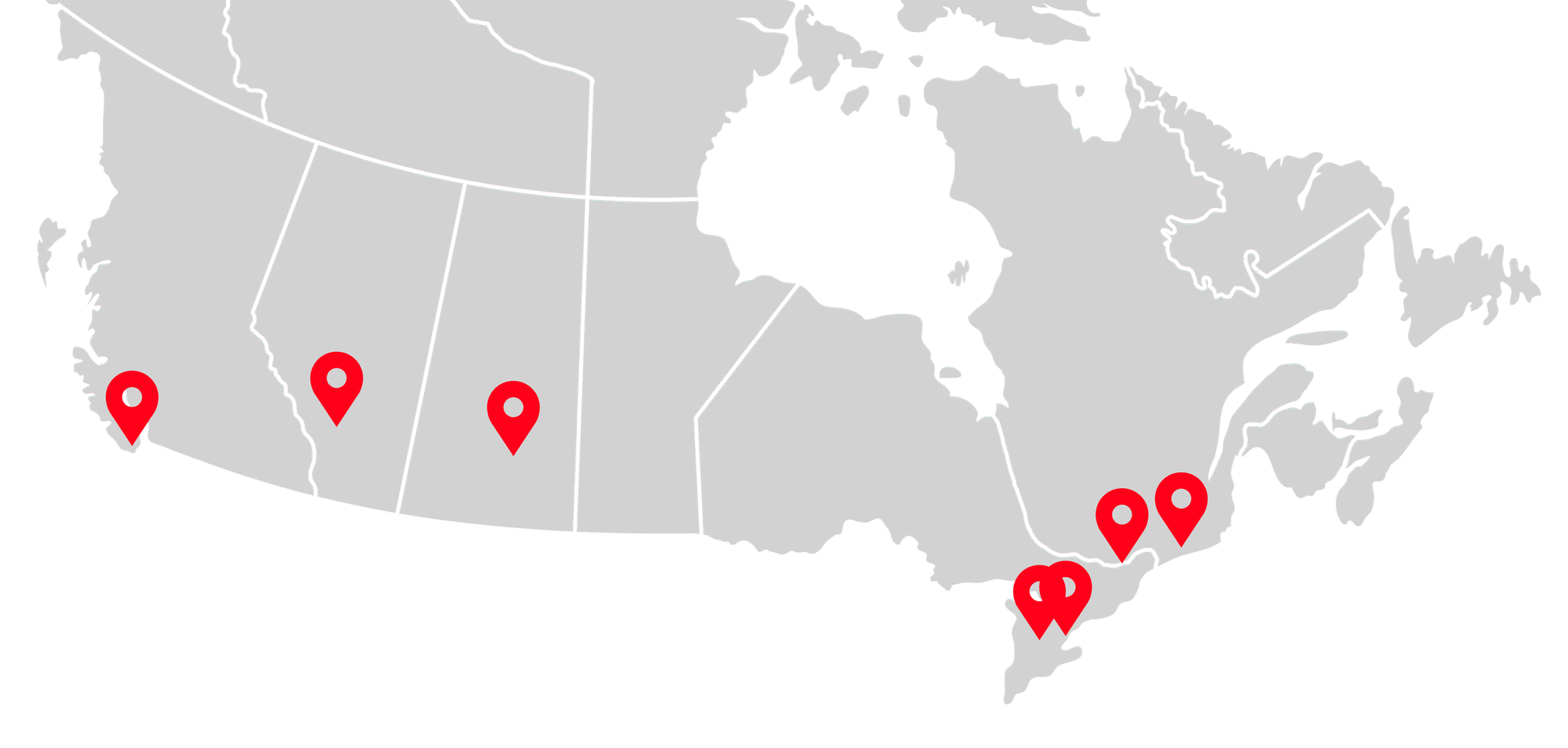

Cascade Presence

Cascade Institute researchers can be found across Canada:

Cascade Presence

Cascade Institute researchers can be found across Canada: